Over the past two weeks I have published posts dealing with issues that arouse in Israel’s 1st Digital Diplomacy Conference held earlier this year in Tel Aviv. This week’s post offers insight into an additional issue that was debated by scholars and practitioners who attended the conference- diplomats’ need to engage with social media followers.

When they first migrated to social media, many scholars expected that MFAs would use such platforms in order to converse with online publics. Digital diplomacy was seen by many as the very manifestation of the “new” public diplomacy, one that focused on building relationships with foreign populations rather than influencing them.

Nearly a decade after MFAs’ migration to social media, it is evident that the revolution has not been tweeted or Facebooked. The majority of MFAs do not regularly converse with their followers nor do they respond to their comments, answer their questions or supply information when requested. As I argued in a recent study, social media engagement is restricted to online QA sessions that are limited in scope and duration.

As such, it is my contention that online engagement remains the Achilles heel of diplomats and diplomatic institutions.

Interestingly, some MFAs now openly question the need to engage with social media followers. If Facebook and twitter can be used for information dissemination and influence, why bother with answering tough questions or replying to open criticism? Others argue that engagement should be practiced only when fitting- such as when coordinating an online response to natural disasters.

In this post I offer six reasons why MFAs should engage in open conversations with their followers.

1. Because social media followers are eager to converse with diplomats and MFAs

The first and perhaps most significant reason to practice MFA-public engagement is that people are eager to converse online with diplomats. This is evident when examining the number of comments and questions published in response to MFA social media content.

For instance, I recently analyzed the Facebook activity of the US State Department during the month of January 2016. My analysis revealed that during January the Department published 146 Facebook posts. Remarkably, the average post garnered 65 comments from social media followers. Moreover, 12% of the posts received more than 100 comments. However, my analysis also revealed that during that month, the Department did not respond to any of these comments nor did it answer followers’ questions. This is by no means a novel finding. Scholarly work focusing on social media has demonstrated time and again that MFAs fail to converse with online publics.

2. Because social media followers may soon leave MFAs’ profiles

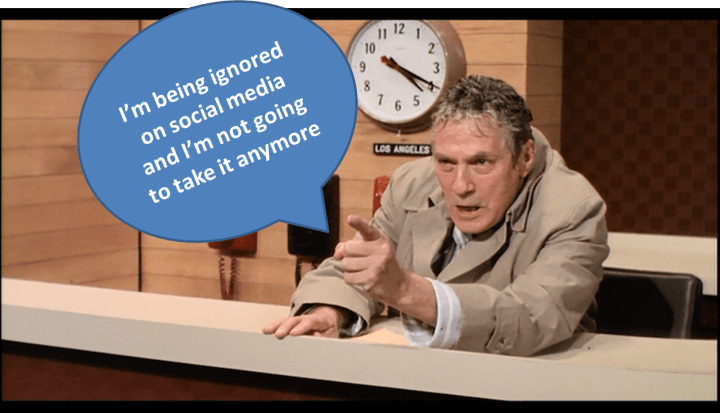

Social media followers expect MFAs and diplomats to engage with them on social media. This is due to the fact that relationships are the foundation of social networking sites, especially Facebook. By failing to meet the needs, and expectations, of social media followers MFAs risk losing their online audiences. Indeed social media followers who feel ignored, and who are spoken at rather than with, may soon abandon MFA profiles without bothering to return. When this happens, MFAs will have forfeited the opportunity to foster relations with a globally connected public sphere.

3. Because followers’ can provide MFAs with an abundance of information

Social media engagement consists of two crucial components: talking and listening. By conversing with their followers, MFAs can learn how their nations are viewed by foreign populations; how their policies are received in other countries and to what extent online audiences are receptive to MFA messages. Thus, social media engagement may offer a breadth of insight for foreign policy makers. Dialogic engagement may be conceptualized as an especially ethical form of communication as it holds benefits for both MFAs and their online followers who are well informed, opinioned and clamoring to be heard.

4. Because social media engagement can lead to the creation of networks

Many scholars, and diplomats, have argued that in the 21st century achieving diplomatic goals rests on one’s ability to form goal-oriented networks. While such networks aim at achieving offline goals (i.e. removing landmines), they may be formed and managed online. Yet one cannot create, or partake, in networks without contributing to them. If MFAs want to harness social media’s potential to create global networks of influence and advocacy they are going to have to transition from monologue based diplomacy to dialogue based diplomacy.

5. Because diplomats have amazing insights into our world

I once tried to argue that the WikiLeaks scandal actually benefited diplomats. Indeed many of the people who read the leaked documents came to the conclusion that diplomats are well informed, intelligent and analytical. As such, diplomats may offer social media followers insight about their home countries, the countries in which they have served and global events shaping our world. At a time when we are bombarded with contradicting information, and struggling to make sense of our world, diplomats can serve as talented online guides.

Yet they are prevented from doing so given the rhetoric of influence that is still commonplace within MFAs. Indeed when social media gurus and communication experts encourage diplomats to venture online, they speak only of the medium’s ability to influence foreign populations. However, influence leads to monologue and disregard to dialogue. If MFAs truly wish to maximize their use of social media, and empower online diplomats, they must abandon the rhetoric of influence which is a remnant of 20th century diplomatic practice.

6. Because it is disingenuous to use social media for monologue

Social networking sites were originally created to facilitate social interaction. And although they have since morphed into news providers, retailers and digital stalkers, many still view these sites as inherently social. But social interaction rests on two-way sharing of information. By only speaking at people, MFAs are breaking the “social media contract” that exists between SNS users. There is something disingenuous about using social media to become part of a global community while refusing to contribute to that community.

And that’s exactly what MFAs are doing.

Summary

I feel it important to state that I do not expect MFAs to dedicate all their resources to constantly conversing with online publics. That would be too demanding and unrealistic. Yet if they are to meet the potential of digital diplomacy, MFAs have to dedcicate some resources to conversing with their followers. That means open conversations that are not limited to one issue. It also means responding to criticism and sharing information.

It is equally important to remember that such activities are not new- diplomats have been conversing with people for five centuries.