When researching digital diplomacy, one soon realizes that every foreign ministry (MFA) has undergone a unique process of digitalization. The digitalization of the US State Department rested, among other, on the appointment of two digital enthusiasts- Alec Ross and Jared Cohen. Canada’s digitalization was facilitated by a change in administration as the Trudeau government urge diplomat to join online conversations. The Crimean Crisis led the German MFA to restructure its strategic communications department. New Zealand’s MFA sought to adopt digital technologies following the example of other government ministries while Lithuania wished to communicate with Diasporas and reverse a possible ‘Brain Drain’.

Even today the practice of digital technology is not uniform. Some nations conduct network analyses to assess their international image. Other ministries prioritize countering disinformation and preventing the circulation of conspiracy theories. The Israeli MFAs uses social media to interact with Arab users while Palestine has created a virtual Embassy to Israel. And while Kenya, Ethiopia and Rwanda all rely on digital forums to interact with their Diasporas, the Polish MFA dedicates time and effort to distancing Poland from the Holocaust.

Even the pace of digitalization varies from ministry to ministry. Some ministries, such Israel and Lithuania, were quick to set up digital units and master technologies once they decided to migrate online. Others have undergone a slower process. Sweden, once a digital pioneer, no longer spearheads the digitalization of diplomacy. This diversity begs the question- how will Covid19 impact MFAs’ digitalization?

New Frontiers: From Virtual Reality to Artificial Intelligence

Hanaa Arendt said that everything that happens once is destined to happen again. The reason being that events serve as precedents that guide societies and governments. Covid19 has disrupted diplomatic activities on all levels. Embassies, for example, were shut down due to local lockdowns forcing diplomats to Zoom and resolve consular issues from their homes. MFAs also transitioned to emergency mode focusing primarily on repatriating citizens, while public diplomacy activities received minimal attention. In multi-lateral institutions, virtual meetings and deliberations replaced face-to-face meetings. This had a considerable impact on multi-lateral diplomacy as UN coalitions are built in hallways and between sessions. Even G7 leaders had to interact remotely, a problem as body language often steers meetings between leaders.

Covid19 will surly pass, be it in 2020 or 2021. Yet the precedent of Covid will have a prolonged influence on diplomacy. Any future pandemic, even one that poses a minimal risk, may prompt nations to initiate lockdowns, limit human contact and reduce international travel. Indeed, future governments will dread repeating the mistakes of Covid be it due to political or ethical reasons. MFAs must therefore begin preparing today for the next diplomatic shutdown.

Some have argued that virtual reality may prove useful in this endeavor. Members of the UN Human Rights committee will convene in a virtual environment where their avatars will confrere with one another. Similarly, Embassies and MFAs will continue their work from home while holding virtual reality meetings. Some have postulated that such use of virtual reality will arrive sooner than later. To examine this argument, I interviewed an Israeli academic who is pioneering virtual reality studies.

According to my interviewee, the application of virtual reality will take some time. First, while virtual reality is more immersive, it is yet to offer experiences that transports a user to a fully interactive virtual realm. Second, there is lack of advanced hardware. ‘The tools we have now are like the iPhone 1′ he said. Moreover, companies have yet to market affordable virtual reality equipment. Finally, virtual reality will come of age when it becomes widespread among the population. Indeed, one could only enjoy the iPhone 1 if his peers had cell phones of their own.

Another technology that might be pursued by MFAs is artificial intelligence (AI). Here the goal is not to replace offline activity but to help manage MFA resources. For instance, Corneliu Bjola has found that the Lithuanian MFA used a chat-bot that could automatically answer consular questions. This reduced Lithuanian diplomats’ workload enabling them to focus on other issues. AI could prove useful in future Covid-like events as MFAs could automatically gather and analyze global news reports on the pandemic thus predicting its spread pattern. This would greatly impact repatriation efforts and consular activities. AI could also be used to automatically create social media content that emphasizes national efforts and success stories.

Who Will Get Their First?

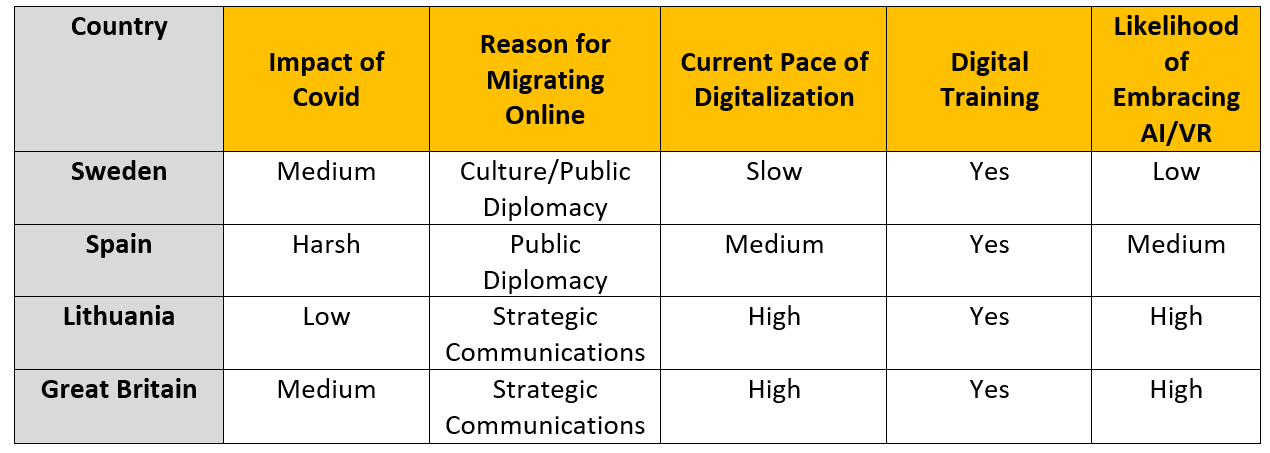

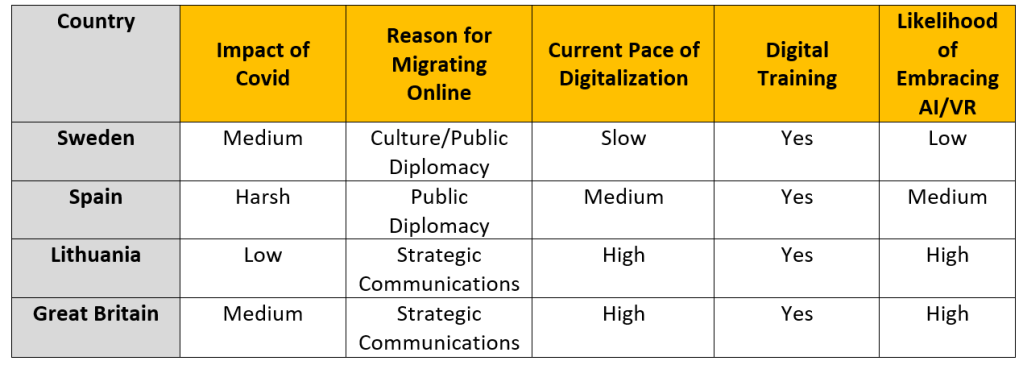

Both AI and virtual reality would need to be mastered by diplomats and MFAs at present, if they are to be used in the future. Importantly, MFAs could begin collaborating today with commercial companies that specialize in said technologies. Table 1 lists several variables that can help anticipate which MFAs will begin investing in future technologies.

Table: Factors that may influence MFAs’ adoption of new technologies

Table 1 suggests that the national impact of Covid may determine diplomats’ investment in the next wave of technologies. Indeed, Italy, Spain and others who lost tens of thousands of citizens may realize the need for digital diplomatic infrastructure (e.g., virtual reality helmets). Next, an MFA’s motivation for migrating online may also be important. Those MFAS that simply wish to brand their nation will be late adopters of such technologies. However, the most important factors are Current Pace of Digitalization and Digital Training. Those MFAs that have become accustomed to embracing new technologies, and to implementing such technologies through digital training, will be most likely to prepare for the future ‘Covids’.