Now is the age of nostalgia. Throughout the world we are witnessing an insatiable longing for the past. In the post-Brexit haze, the UK craves the influence and power of its defunct empire; in Turkey neo-Ottoman sentiments have transformed a President into a Sultan; In America, many still hope to Make America Great Again while in Poland and Hungary leaders are preying on nationalist sentiments to rebuild homogenous societies. Even Berliners increasingly romanticize East Germany’s austerity and fabled social cohesion.

The age of nostalgia is nowhere more evident than in cultural products. Contemporary films such as The King’s Speech, Dunkirk and Their Finest Hour all celebrate the last stand of the British Empire while Kingsman transports the English gentleman into the 21st century thus offering a sense of continuity. Reincarnations of Indiana Jones, Star Trek and Star Wars all forcefully summon the past to the present while television shows such as Deutschland 83 and The Queen’s Gambit fetishize the ideological certainty of the Cold War. Similarly, new seasons of Full House and Gilmore Girls offer viewers a taste of the blasé mindset of the 1990’s.

Nostalgia is but a response to the volatility and unpredictability of the digital world, one in which truth, reality and traditions are contested. Truth is contested as narratives have supplanted facts as the organizing structure of news and government communication. Reality is contested as it is now algorithmically tailored to the world view of social media users. Reality has thus been fractured into billions of pieces. Traditions are contested as revolutionary ideas easily transcend national borders bringing with them changes to well established norms, values and social structures such as families.

Within the world of digital diplomacy, nostalgia has become a familiar trope. At times, diplomats and MFAs use nostalgic tropes to summon the past and make sense of a chaotic presence. This is quite evident when MFAs discuss an “AI Arms Race” or hint that today’s “Chip Wars” will results in “A New Cold War”. From a nostalgic perspective, both the Arms Race and the Cold War that marked the 20th century are a source of comfort and reassurance. Like hot chocolate on a cold Christmas morning, the binaries of the 20th Century offer an antidote to the angst generated by today’s complex world. The Arms Race was a competition between East and West, between American and Russia and between Capitalism and Communism. It was a world that made sense, one made up of distinct allies and foes, enemies and comrades. Anyone trying to make sense of the cobweb of interests and actors involved in present day conflicts such as the Syrian Civil War, the Russia Ukraine War or the ongoing War in Gaza would fall prey to the allure of simplicity that is at the core of nostalgia.

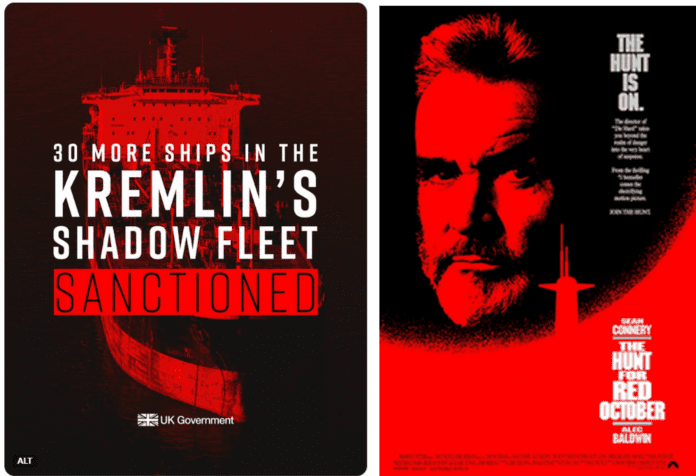

Other times nostalgia is used in domestic digital diplomacy or when diplomats target their own citizenry. Consider for instance the tweet below published by the UK’s Foreign Office announcing sanctions on Russia’s “Shadow Fleet”. Both the wording, and the visual, seem plucked from 1980s or 90s spy dramas centered on the Cold War. This tweet recreates a world of shadows in which “spooks” or spies operate far from prying eyes. The visual resonance between the FCO’s image, and the poster for the Cold War film The Hunt for Red October is remarkable yet also logical if analyzed through the prism of domestic digital diplomacy. British diplomats may be attempting to rally domestic support for the continued opposition to Russia by insinuating that today’s Russia is no different then yesterday’s Russia and that the current struggle against Russia is merely the continuation of the Cold War by other means. Russia is a known foe, and from a nostalgic perspective, the continued hostilities with Russia offer a sense of assurance through continuity and through linking the familiar and binary world of yesteryear with todays’ world. In this way, the FCO’s tweet reduced the complexity of present-day Wars and Crises. The War in Ukraine is simply another stage in the historic struggle against a “Red Russia”, red being the dominant color in the image below.

Finally, nostalgic tropes may be used in digital diplomacy to suggest that modern day struggles shrink in the face of historic ones. In this way, the past is not used to simplify the present but to diminish the sense of threat that the present generates. Such is the case with tweet below published by the US State Department dealing with the “only code in modern military history” not be broken- the America code used in WW2 which was based on Navajo Nation’s code talkers. There is nothing very “modern” about WW2 in that it ended more than 70 years ago yet from a nostalgic perspective WW2 remains a central reference point in many nations. The reason being that it serves as a reminder that nations can meet great challenges, the great adversities can be overcome and that nations know how to rally in a time of crisis. Through nostalgia the bitter political divisions that mark the present are obscured. It is in this way that nostalgia can strengthen feelings of social cohesion and a sense of connectedness with others at a time of great solitude as people are algorithmically confined and isolated in their feeds.

Of course, nostalgia is always divorced from reality. Nostalgia is highly selective and skewed re-telling of the past, a re-telling that transforms fears into comforts and crises into opportunities. The tweet from the State Department uses nostalgia to suggest that Native Americans were an integral part of some illusionary “Great” American society in the 1940s. A distorted telling of American history. Yet the more complex and unintelligible the world becomes the more nostalgia becomes a potent device for sensemaking in both politics and in diplomacy. The risk is that nostalgic tropes in digital diplomacy ultimately lead to stronger nostalgic sentiments in society, sentiments that are always accompanied by a desire to resurrect the world of old and to do away with the world of today. This is achieved by supporting radical movements that promise to make the world “Great Again”. Yet the “Great World” is one of isolationism, nationalism and a contempt for multilateralism. Nostalgia is thus the undoing of diplomacy, a dangerous tool in diplomat’s digital arsenal.

For more on Nostalgia’ Role in Digital Diplomacy view my paper “The Selfie as Perpetual Nostalgia: Analyzing Russia’s Selfie Diplomacy in 2020” below

Historian Eric Hobsbawm dedicated much of his academic work to exploring the impact of the past on present-day societies. For Hobsbawm, the past was always present. Yet the function that the past plays in the present could differ greatly. During times of upheaval, the past can serve as a roadmap or template for overcoming adversity. During times of crises, the past can offer a reminder of societal resilience and thus provide hope and comfort. During times of disruption and innovation, the past plays a central role in generating a sense of nostalgia and a deeply felt yearning for the ‘good old days’.

Historian Eric Hobsbawm dedicated much of his academic work to exploring the impact of the past on present-day societies. For Hobsbawm, the past was always present. Yet the function that the past plays in the present could differ greatly. During times of upheaval, the past can serve as a roadmap or template for overcoming adversity. During times of crises, the past can offer a reminder of societal resilience and thus provide hope and comfort. During times of disruption and innovation, the past plays a central role in generating a sense of nostalgia and a deeply felt yearning for the ‘good old days’.

The rapid and consecutive launch of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools over the past two years has generated a global frenzy. Large language models such as ChatGPT and Gemini have already amassed hundreds of millions of users and have been hailed as ushering in a new technological era marked by limitless data-driven insight and creativity. Global internet users have spent millions of hours interacting with Chatbots which offer companionship, emotional support and a humorous escape from daily life. Activists, artists and influencers have swiftly embraced AI image generators to create a stunning array of new visuals, including that of the Pope in a Puffer coat. This global frenzy has catapulted the worth of AI-related companies to the top of global markets with relatively new companies, such as OpenAI, being valued at $157 billion, and established companies, such as Nvidia, reaching a valuation of $3.4 trillion. Each new day brings with it new AI startups that promise to revolutionize healthcare, finance, transportation, education and e-commerce.

The rapid and consecutive launch of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools over the past two years has generated a global frenzy. Large language models such as ChatGPT and Gemini have already amassed hundreds of millions of users and have been hailed as ushering in a new technological era marked by limitless data-driven insight and creativity. Global internet users have spent millions of hours interacting with Chatbots which offer companionship, emotional support and a humorous escape from daily life. Activists, artists and influencers have swiftly embraced AI image generators to create a stunning array of new visuals, including that of the Pope in a Puffer coat. This global frenzy has catapulted the worth of AI-related companies to the top of global markets with relatively new companies, such as OpenAI, being valued at $157 billion, and established companies, such as Nvidia, reaching a valuation of $3.4 trillion. Each new day brings with it new AI startups that promise to revolutionize healthcare, finance, transportation, education and e-commerce.