Starting in 2011, a new generation of diplomats began using social media to get their message out. So what has changed with e-diplomacy since then?

Drafting a tweet, a Facebook post, or a blog post will become a part of the routine duty for modern diplomats. Pictured: Russia’s Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (R) and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. Photo: Reuters

The peak of e-diplomacy occurred in 2011-2012, bringing with it widespread attention to a new generation of diplomats using social media to get their message out. In both Russia and the West, new terms emerged to capture this phenomenon: the U.S. State Department coined the term 21st Century Statecraft; the UK Foreign Office created the term Digital Diplomacy; and Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs used the term Innovative Diplomacy.

So what has changed since then? Does e-diplomacy have as promising future as it appeared a couple of years ago?

The state of e-diplomacy today

Today, diplomats use Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and country-specific social media networks such as Russia’s VKontakte or China’s Weibo.

Eighty-two foreign ministries currently have Twitter accounts, and 47 ministers of foreign affairs are personally on Twitter. The two most popular foreign ministers on Twitter are Abdullah bin Zayed (@ABZayed) of the United Arab Emirates and Turkey’s Ahmet Davutoğlu (@Ahmet_Davutoglu) – each with more than 400,000 followers. In third place is Sweden’s minister Carl Bildt (@CarlBildt) with over 246,700 followers.

Only three years ago, this kind of diplomacy was considered rather extraordinary. Historically, diplomacy was a cautious and circumspect endeavor, with meetings conducted mostly behind closed doors.

Now e-diplomacy tools have become a core part of public diplomacy, which has its goal establishing contacts with a target online audience and then directly addressing this audience with specific messages anywhere in the world.

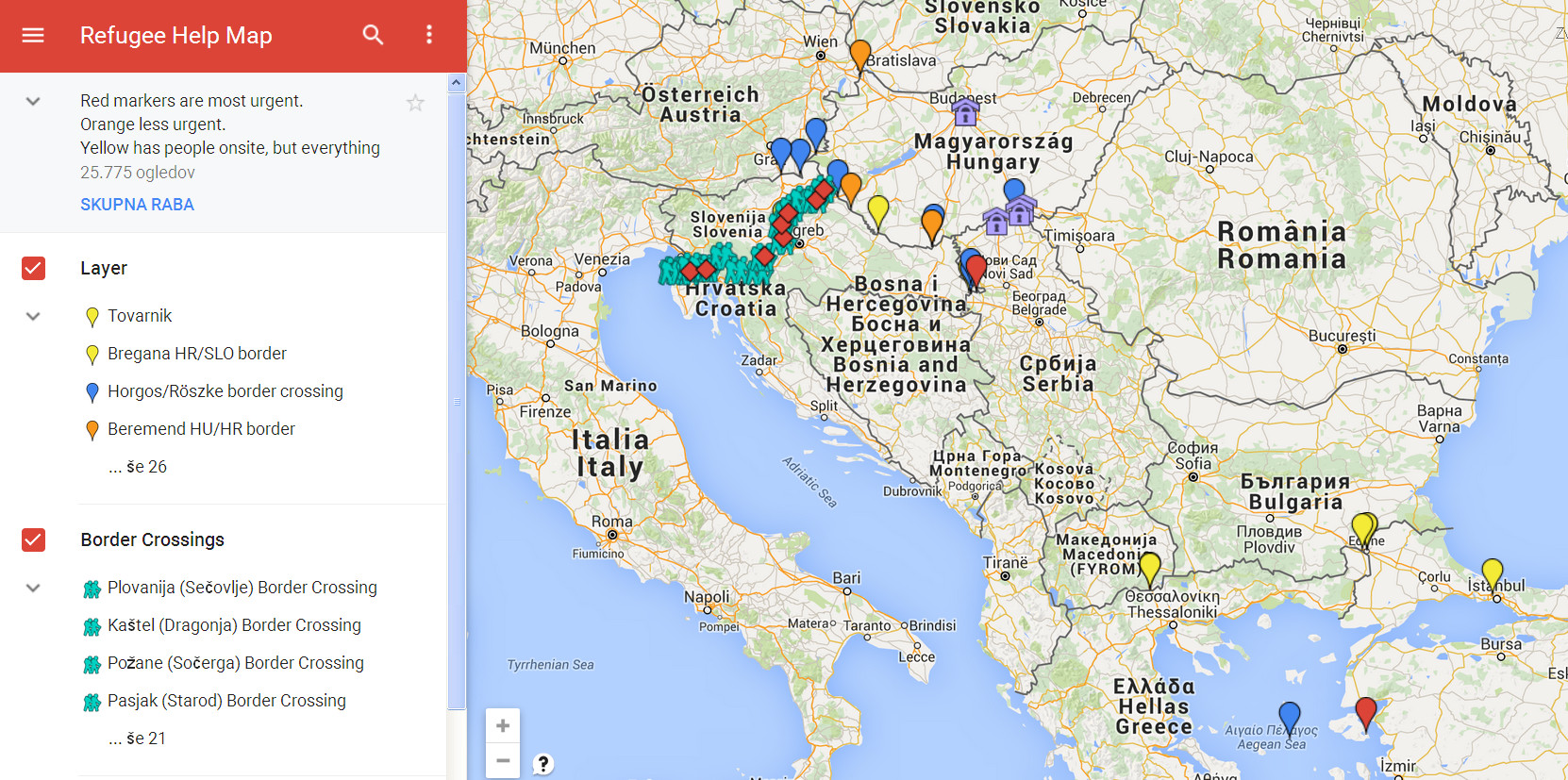

However, e-diplomacy is much more than mere public diplomacy. It also represents a form of information management, or the management of knowledge and experience accumulated by foreign ministries. In consular affairs, e-diplomacy tools simplify processing of visa documents and facilitate direct contacts with citizens abroad. And last but not the least, in the occurrence of emergencies and natural disasters, e-diplomacy tools become particularly useful, providing foreign citizens a means of communication with their state embassies or consulates.

U.S. and e-diplomacy

Today, the United States leads the way in digital diplomacy. The U.S. State Department has had an office of e-diplomacy since 2003, but it was Hillary Clinton who took it to a completely new level. In 2009, she launched “21st Century Statecraft,” a program that was designed to complement traditional foreign policy tools with new innovations in statecraft that fully leverage the networks and technologies of an interconnected world.

As a result, the State Department essentially become a global media domain managing 288 Facebook pages with 12.9 million fans; 196 Twitter accounts with 1.9 million followers; and 125 YouTube channels that have racked up 16.3 million views.

However, digital diplomacy doesn’t seem to be improving America’s image abroad. According to a 2013 BBC survey, U.S. popularity declined seven percentage points – from 47 to 40 percent – from 2009 to 2012. In fact, America’s popularity worldwide is now as low as when President Bush left office in 2009.

It’s quite possible that’s why Hillary Clinton’s successor, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, still prefers offline diplomacy over online. In March 2013 in his briefing he emphasized, “The term digital diplomacy is almost redundant – it’s just diplomacy, period.” Kerry’s Twitter and Facebook accounts – last updated in 2012 – are dormant.

Russia and e-diplomacy

The Department for Information and Press of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs carries out online communication on the Internet and manages Russia’s growing social media presence. In 2011, an official Twitter account of the Ministry was launched, and in 2012, an official YouTube account (“midrftube”) was opened to the public. Whereas America’s “21 Century Statecraft” is a strategic platform, announced and published online, Russian digital diplomacy remains something still undefined.

Since February 2013, the Ministry has had a Facebook page with about 13 thousand subscribers. If on Twitter and YouTube, the Ministry’s content is represented in both Russian and foreign languages, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ account on Facebook remains solely in Russian, thus potentially limiting the target audience of social media accounts outside of Russia and the post-Soviet space.

In contrast, the U.S. State Department communicates with a Russian audience on Facebook in Russian. It also has 10 official Twitter feeds in Arabic, Chinese, English, Farsi, French, Hindi, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Turkish and Urdu. Most of the Foreign Ministries over the world communicate with their audience in English. Most of Russians embassies and consulates carry out communications in English and the languages of the host countries, so it makes sense also to have a social media presence in English.

Does e-diplomacy still have a promising future?

Looking ahead, e-diplomacy will be integrated into the way nations interact with each other. Drafting a tweet, a Facebook post, or a blog post will become a part of the routine duty for modern diplomats.

Two years ago, e-diplomacy had only a few supporters. Those were Alec Ross, Clinton’s senior advisor for innovation, and Jared Cohen, a member of her policy planning staff.

Since then, new players in the e-diplomacy field have emerged including Digital Director of the Israeli Embassy in Washington Jed Shein, Head of Digital diplomacy at the British Embassy in Washington Scott Nolan Smith, Maria Zakharova, Deputy Director of the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Information and Press Department, and others.

As e-diplomacy expands, it will obtain more supporters and champions across continents and countries. For its further development and implementation across the world, e-diplomacy practitioners will have to keep in mind the changing nature of social media.

This means that a digital diplomacy strategy needs to be as simple and clear as possible so that it can be adapted in real-time. It also means that foreign ministries need to realize that the message in social media cannot always be controlled. Going forward, the driving engine of e-diplomacy will be the young generation of diplomats who grew up using social media platforms everyday.