By Paul Rockower

It is fitting that a magazine devoted to studying innovations and trends in the field of public diplomacy has turned its focus on an increasingly popular forms of cultural diplomacy: gastrodiplomacy.

Public Diplomacy Magazine’s Summer 2009 issue on Middle Powers explored the behavior of middle powers and the contours of “middlepowermanship.” Articles in this issue outlined how emerging countries are using public diplomacy more prominently to break out of a crowded field of competing nations. Meanwhile, the issue on cultural diplomacy looked at the various means that countries used to communicate their idiosyncratic cultures, ranging from Japan’s use of Anime cartoons to conduct cultural diplomacy, to how Nigeria made their culture a continental phenomenon, through the Nigerian film industry, Nollywood. Both editions led the way towards a better understanding of the field of public diplomacy, and helped create the space in which gastrodiplomacy is beginning to be understood.

Public Diplomacy Magazine’s Summer 2009 issue on Middle Powers explored the behavior of middle powers and the contours of “middlepowermanship.” Articles in this issue outlined how emerging countries are using public diplomacy more prominently to break out of a crowded field of competing nations. Meanwhile, the issue on cultural diplomacy looked at the various means that countries used to communicate their idiosyncratic cultures, ranging from Japan’s use of Anime cartoons to conduct cultural diplomacy, to how Nigeria made their culture a continental phenomenon, through the Nigerian film industry, Nollywood. Both editions led the way towards a better understanding of the field of public diplomacy, and helped create the space in which gastrodiplomacy is beginning to be understood.

The Genesis of Gastrodiplomacy

Gastrodiplomacy represents one of the more exciting trends in public diplomacy outreach. The subject of culinary cultural diplomacy—how to use food to communicate culture in a public diplomacy context—began with the application of academic theories of public diplomacy to case studies in the practice of the cultural diplomacy craft.

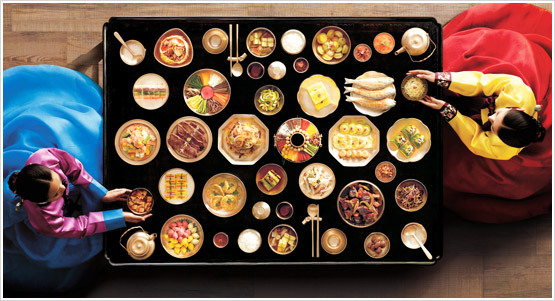

Gastrodiplomacy was borne out of pinpointing case studies in the field and connecting these cases to a broader picture. An obscure word in an obscure article about Thailand’s outreach to use its restaurants as forward cultural outposts as a means to enhance its nation brand has become a field of study within the expanding public diplomacy canon. The highlighting of disparate case studies such as South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Peru, among others,[1] led to patterns of practice; patterns led to broader pictures of trends that proved an innovative means of conducting successful cultural diplomacy.

Scholars of gastrodiplomacy have remained cognizant of the manner in which food has shaped both world history and diplomatic interactions. Mary Jo Pham notes:

Throughout history, food has played a significant role in shaping the world, carving ancient trade routes and awarding economic and political power to those who handled cardamom, sugar, and coffee. Trade corridors such as the incense and spice route through India into the Levant and the triangular trade route spanning from Africa to the Caribbean and Europe laid the foundations for commerce and trade between modern nation-states. Indeed, these pathways encouraged discovery—weaving the cultural fabric of contemporary societies, tempering countless palates, and ultimately making way for the globalization of taste and food culture.[2]

There are few aspects as deeply or uniquely tied to culture, history, or geography as cuisine. Food is a tangible tie to our respective histories, and serves as a medium to share our unique cultures.

The most effective cultural diplomacy takes national traits and cultures, distills them to their most tangible forms, and communicates them to audiences abroad. Like the successful use of music as cultural diplomacy, gastrodiplomacy also seeks to create a tangible, emotional and trans-rational connection.[3] Both music and food work to create an emotional and transcendent connection that can be felt even across language barriers. Gastrodiplomacy seeks to create a more oblique emotional connection via cultural diplomacy by using food as a medium for cultural engagement. On this emotional connection, Rachel Wilson comments:

The most effective cultural diplomacy takes national traits and cultures, distills them to their most tangible forms, and communicates them to audiences abroad. Like the successful use of music as cultural diplomacy, gastrodiplomacy also seeks to create a tangible, emotional and trans-rational connection.[3] Both music and food work to create an emotional and transcendent connection that can be felt even across language barriers. Gastrodiplomacy seeks to create a more oblique emotional connection via cultural diplomacy by using food as a medium for cultural engagement. On this emotional connection, Rachel Wilson comments:

Because we experience food through our senses (touch and sight, but especially taste and smell), it possesses certain visceral, intimate, and emotion qualities, and as a result we remember the food we eat and the sensations we felt while eating it. The senses create a strong link between place and memory, and food serves as the material representation of the experience.[4]

As such, gastrodiplomacy understands that you don’t win hearts and minds through rational information, but rather through indirect emotional connections. Therefore, a connection with audiences is made in tangible sensory interactions as a means of indirect public diplomacy via cultural connections. These ultimately help to shape long-term cultural perceptions in a manner that can be both more effective and more indirect than targeted strategic communications.

Theories of Gastrodiplomacy

In offering a theoretical construction for the field of gastrodiplomacy, it is necessary to define the framework. This author highlights the characteristics of gastrodiplomacy by comparing it to the practice of culinary diplomacy.[5] In drawing distinctions to the field, the author notes the equivalence of diplomacy to public diplomacy, thusly culinary diplomacy is to gastrodiplomacy.[6] While diplomacy involves high-level communications from government to government, public diplomacy is the act of communication between governments and non-state actors to foreign publics. Similarly, this author defines culinary diplomacy as the use of food for diplomatic pursuits, including the proper use of cuisine amidst the overall formal diplomatic procedures. Thus, culinary diplomacy is the use of cuisine as a medium to enhance formal diplomacy in official diplomatic functions such as visits by heads-of-state, ambassadors, and other dignitaries. Culinary diplomacy seeks to increase bilateral ties by strengthening relationships through the use of food and dining experiences as a means to engage visiting dignitaries.

In comparison, gastrodiplomacy is a public diplomacy attempt to communicate culinary culture to foreign publics in a fashion that is more diffuse; it takes a wider focus to influence the broader public audience rather than high-level elites. Gastrodiplomacy seeks to enhance the edible nation brand through cultural diplomacy that highlights and promotes awareness and understanding of national culinary culture with wide swathes of foreign publics. Moreover, as public diplomacy in the age of globalization transcends state-to-public relations and increasingly includes people-to-people engagement, gastrodiplomacy also transcends the realm of state-to-public communication, and can also be found in forms of citizen diplomacy.

Gastrodiplomacy should not be confused with international public relations campaigns to promote various national food products. Simply promoting a food product of foreign origin does not mean that such promotions constitute gastrodiplomacy. Rather, gastrodiplomacy remains a more holistic approach to raise international awareness of a country’s edible nation brand through the promotion of its culinary and cultural heritage. Gastrodiplomacy also differs from food diplomacy, which involves the use of food aid and food relief in a crisis or catastrophe. While food diplomacy can aid a nation’s public diplomacy image, it is not a holistic use of cuisine as an avenue to communicate culture through public diplomacy.[7]

Gastrodiplomacy 2.0: Poly- and Para-

Thus far, most gastrodiplomacy case studies come from states defined as “middle powers.” Middle powers are that fair class of states that neither reign on high as superpowers nor reside at the shallow end of the international power dynamic, but exist somewhere in the vast muddled middle of the global community.[8]

Public Diplomacy Magazine’s issue on middle powers explored the hallmarks and techniques of middle powers and how they navigate the fight through the congested swathe of states in the middle of the pack in the global system. In writing about the challenges facing middle powers, Eytan Gilboa notes:

Peoples around the world don’t know much about them, or worse, are holding attitudes shaped by negative stereotyping, hence the need to capture attention and educate publics around the world. Since the resources of middle powers are limited, they have to distinguish themselves in certain attractive areas.[9]

States like Norway and Qatar focused on niche areas like conflict resolution.[10] Others middle power states, like South Korea and Taiwan, have pushed to raise their nation brands through the arts, music, and cuisine that make their respective cultures unique.[11]

There are a number of difficulties that middle powers share in regards to their visibility issues on the global stage. Middle powers face the fundamental challenge of recognition in that global publics are either unaware of them, lack nuance or broad understanding, or hold negative opinions—thus requiring the need to secure broader global attention. As culinary cultural diplomacy scholars have learned through the emergence of the field, gastrodiplomacy helps under-recognized nation brands increase their cultural visibility through the projection of national or regional cuisine.

Yet it is not middle powers alone that are conducting gastrodiplomacy now. In 2012, the U.S. Department of State embarked on its own culinary cultural diplomacy campaign: the Diplomatic Culinary Partnership. The Diplomatic Culinary Partnership includes equal parts culinary diplomacy—through the creation of an American Chef Corps to help engage with the State Department in formal diplomatic functions—and gastrodiplomacy—through sending out the American Chef Corps to embassies and consulates around the globe to conduct public diplomacy programs using food to engage with foreign publics. Additionally, the program facilitates people-to-people cultural exchanges through the International Visitors Leadership Program (IVLP) in chef exchanges in the United States.

If gastrodiplomacy conducted by middle powers was about using culinary cultural diplomacy to enhance the nation brand, then gastrodiplomacy conducted by great powers (the U.S., China), or culinary great powers like France, becomes more focused on illustrating and deepening nuance in the edible nation brand.

Unlike many middle powers seeking to simply highlight their edible nation brand as a means to increase their visibility, the visibility of the U.S. is not in question. Rather, the strategy of the U.S. gastrodiplomacy campaign is to create nuance and understanding so that the American edible nation brand is seen as more than fast food dishes and giant consumer chains, and includes a deeper understanding of regional differences. Thus there is less a need to highlight the cuisine as a whole, but rather a need to focus on the various regional and local dimensions that offer uniqueness. To this end, distinctive cuisines like Cajun cuisine from New Orleans, or cuisine from the Pacific Northwest, become the object of America’s gastrodiplomacy focus.

As gastrodiplomacy moves forward as a field, we can expect two trends to become more prevalent: 1) gastrodiplomacy polylateralism and; 2) gastrodiplomacy paradiplomacy. The term “polylateralism,” coined by diplomacy scholar Geoffrey Wiseman, refers to the interaction of states with non-state actors in the realm of diplomacy or public diplomacy.[12] Gastrodiplomacy is one area of public and cultural diplomacy where states are starting to work with non-state actors through public/private initiatives, such as the U.S. State Department’s Diplomatic Culinary Partnership—a public/private initiative that includes a partnership with the nonprofit James Beard Foundation.[13]

Another initiative that has taken on elements of polylateral gastrodiplomacy is the Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck. Given that the Ottoman Empire had its first coffee shop in the Sublime Porte’s capital Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1554, many centuries before Starbucks ever roasted a bean, the Turkish coffee campaign to educate audiences on the history and flavor of Turkish coffee is smart gastrodiplomacy.

The Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck began its gastrodiplomacy outreach in 2012 by handing out free cups of Turkish coffee up and down the East Coast of the United States, making stops in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. The campaign handed out cups of hot, sweet Turkish coffee with the grinds at the bottom, while an education component of the campaign informed audiences about the historical connection of coffee to Turkish culture. The campaign also included fun cultural diplomacy events, like fortune telling from the coffee grounds in the cups.[14] The Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck is conducting a second round of outreach, this time in Europe with stops in Holland, Belgium, and France.

The Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck campaign in the U.S. was conducted initially as a private venture with sponsorship from Turkish-American businesses, the American-Turkish Association, the Turkish coffee company Kurukaheveci Mehmet Efendi and Turkish Airlines—as well as some support from the Turkish Embassy to the U.S. and Consulates. The program’s success led to its second iteration in Europe, launched in a more polylateral gastrodiplomatic fashion as a public/private initiative, including the support of the representative offices of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Meanwhile, with the increased prevalence of “paradiplomacy,”[15] the phenomenon of sub-state actors conducting their own international diplomatic engagements, the necessity for these sub-state actors to also engage in public and cultural diplomacy has become more pronounced. Already some sub-state actors are conducting cultural diplomacy. In international forums like the Taipei Flora Expo in 2011, the State of Hawaii conducted its own pavilion separate from that of the U.S. Pavilion as a means to showcase Hawaii’s unique flora and fauna. In addition, numerous sub-state regions conduct their own gastrodiplomacy at various food fairs to exhibit their unique culinary heritages.

The positive side of paradiplomacy engaging in gastrodiplomacy is that it makes cultural diplomacy significantly more localized. To make public diplomacy more successful as a field, it remains incumbent on local communities to understand their role in communicating culture. Creating sub-state buy-in can ultimately strengthen gastrodiplomacy initiatives and make more local communities realize their role in public, cultural, and gastrodiplomacy.

Just as gastrodiplomacy helps under-recognized nations expand their brands and cultural visibility through the projection of national or regional cuisine, gastrodiplomacy by sub-state actors helps increase their own uniqueness and brand visibility in a similarly cluttered landscape. As more sub-state actors are starting to conduct paradiplomacy and seeking to strengthen their brand, we can likely expect these actors to turn to gastrodiplomacy as a means to highlight cultural uniqueness of their respective sub-state brands.

One additional trend that is likely to become more common is the use of gastrodiplomacy by non-state actors as a means to conduct public diplomacy and people-to-people diplomacy. Public Diplomacy Magazine has previously examined the role of non-state actors using public diplomacy to promote human rights; in this edition, author Sam Chapple-Sokol examines a number of initiatives, including Conflict Kitchen and Vindaloo against Violence, among others, which have sought to use gastrodiplomacy as a medium to conduct Track 3 Diplomacy. As gastrodiplomacy becomes a more recognized field within public diplomacy, there stands a likelihood of more non-state actors using gastrodiplomacy to facilitate people-to-people diplomacy related to issues of conflict.

Conclusion

Representing one of the newer trends within public diplomacy, gastrodiplomacy has come a long way in a short time. In just a few years, the field of gastrodiplomacy has gone from obscurity to an issue of discussion and debate in academic journals, as well as the subject of its own conference at American University.[16] Gastrodiplomacy embodies a powerful medium of nonverbal communication to connect disparate audiences, and thusly is a dynamic new tactic in the practice and conduct of public and cultural diplomacy.

As more states engage in gastrodiplomacy, new trends will emerge that will shape a new set of best practices in the field, such as increased polylateral partnerships and gastrodiplomacy paradiplomacy, as well as non-state actors turning to gastrodiplomacy as a means to foster people-to-people connections.

References and Notes

[1] For South Korea, see Pham, Mary Jo. “Food as Communication: A Case Study of South Korea’s Gastrodiplomacy.” Journal of International Service 22.1 (2013): Web.; for Taiwan, see Rockower, Paul. “Projecting Taiwan.” Issues and Studies 47.1 (2011): Print.; For Peru, see Wilson, Rachel. “Cocina Peruana Para El Mundo: Gastrodiplomacy, the Culinary Nation Brand, and the Context of National Cuisine in Peru.” Exchange: The Journal of Public Diplomacy 2.2 (2011): Web.

[2] Pham, Mary Jo. “Food as Communication: A Case Study of South Korea’s Gastrodiplomacy.” Journal of International Service 22.1 (2013): Web.

[3] Von, Eschen Penny M. Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2004. Print.

[4] Wilson, Rachel. “Cocina Peruana Para El Mundo: Gastrodiplomacy, the Culinary Nation Brand, and the Context of National Cuisine in Peru.” Exchange: The Journal of Public Diplomacy 2.2 (2011): Web.

[5] For more on the history of culinary diplomacy, see: Chapple-Sokol, Sam. “Culinary Diplomacy: Breaking Breads to Win Hearts and Minds.”The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 8 (2013): Web.

[6] For more on difference between gastrodiplomacy and culinary diplomacy, see Rockower, Paul. “Recipes for Gastrodiplomacy.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 8 (2012): Print.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cooper, Andrew Fenton, Richard A. Higgott, and Kim Richard. Nossal. Relocating Middle Powers: Australia and Canada in a Changing World Order. Vancouver: UBC, 1993. Print.

[9] Gilboa, Eytan. “The Public Diplomacy of Middle Powers.” Public Diplomacy Magazine 1.2 (2009): Print.

[10] On Norway, see: Henrikson, Alan, “Niche Diplomacy in the World Public Arena: The Global ‘Corners’ of Canada and Norway,” in The New Public Diplomacy. New York: Palgrave, 2005. Print.; On Qatar, see: Rockower Paul, “Qatar’s Public Diplomacy,” unpublished paper (2008): Web.

[11] On Korea, see: Jang, Gunjoo, and Won K. Paik. “Korean Wave as Tool for Korea’s New Cultural Diplomacy.” Advances in Applied Sociology 2.3 (2012): n. pag. Print. ; Rockower, Paul. “Projecting Taiwan.” Issues and Studies 47.1 (2011): Print.

[12] Wiseman, Geoffrey, “’Polylateralism’ and New Modes of Global Dialogue” in Diplomacy edited by Crister Jonsson and Robert Langhorne, 36-57. Sage: London, 2004. Print.

[13] Rockower, Paul. “Setting the Table for Diplomacy.” USC Center on Public Diplomacy. 21 Sept. 2012. Web.

[14] Werman, Marco. “Sharing Turkey’s Centuries-Old Coffee Tradition with a Food Truck.”Public Radio International’s The World. 11 May 2012. Web.

[15] Wolff, Steffen, “Paradiplomacy,” Bologna Center Journal of International Affairs 16 (2010): Web.; Tavares, Rodrigo, “Foreign Policy Goes Local,” Foreign Affairs, (2013): Print.

[16] Pham, Mary Jo “Food + Diplomacy= Gastrodiplomacy,” The Diplomatist (2013): Web.; Wallin, Matthew “Gastrodiplomacy— ‘Reaching Hearts and Minds through Stomachs,’” American Security Project (2013): Web.

Paul S. Rockower is a graduate of the USC Masters of Public Diplomacy program. He has worked with numerous foreign ministries to conduct public diplomacy, including Israel, India, Taiwan and the United States. Rockower is the Executive Director of Levantine Public Diplomacy, an independent public and cultural diplomacy organization.

You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.