By Melody Patry / 16 June, 2014

![Read the full report in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]](http://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/brazil-cover.jpg)

This is the third in a series of articles based on the Index report: Brazil: A new global internet referee?

Key debates are under way at international level on internet governance, with crucial decisions up for grabs that could determine whether the internet remains a broadly free and open space, with a bottom up approach to its operation – as exemplified in part by the multistakeholder approach – or becomes a top-down controlled space as pushed for by China and Russia, supported to some extent by several other countries.

In September 2013, the outrage following the revelations of mass surveillance by the US and UK led President Dilma Rousseff to announce that Brazil would host an international summit – NETmundial – on the future of internet governance in April 2014. This internet governance summit – progressive in appearance – took place just two years after Brazil voted in line with countries that have a tradition of internet control at a major international conference on telecommunications in Dubai.

This section looks at Brazil’s attitude in global internet governance debates and the potential contradictions between its domestic and foreign internet policies. In the aftermath of NETmundial and a year before Brazil is to host the 2015 Internet Governance Forum (IGF), this chapter also looks at Brazil’s ability to impose itself as a world leader in internet governance debates.

Is Brazil a swing state on global internet governance? Contradictions between domestic and international policies

What is at stake during the international discussions that shape the evolution and use of the internet has implications for all. The current multistakeholder approach for internet governance supposedly includes civil society and non-governmental actors in decision-making. It is a more bottom-up and multi-layered process, allowing a range of organisations to determine or contribute towards different parts of internet governance. The consultation process at the origin of the Marco Civil law is a possible example of the multistakeholder approach in action: Civil society, private companies, academics, law enforcement officials and politicians participated in the draft.

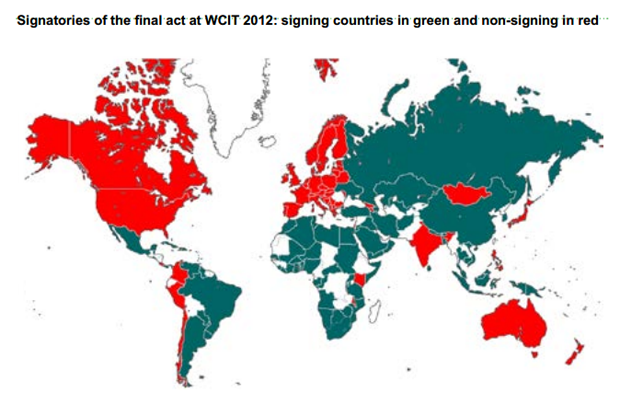

While Brazil has been pushing for stronger internet freedoms lately, especially at the domestic level, it has a history of going in the other direction. In December 2012, Brazil aligned with a top-down approach lobbied by countries that have a tradition of internet control at the Dubai World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) summit. This meeting brought together 193 member states of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in part to decide whether or not and how the ITU should regulate the internet. On one side, EU member states and the US argued the internet should remain governed by an open and collaborative multistakeholder approach. On the other side of the divide, Russia, China and Iran lobbied for greater government control of the net. Brazil, along with the most influential emerging democratic powers (India the notable exception), aligned with this top-down approach.

This decision appeared in total contradiction with Brazil’s defence and implementation of the multistakeholder model at home with Marco Civil (see previous section on Marco Civil da Internet). At the time, the rapporteur of Marco Civil, Alessandro Molon, was opposed to the new ITU regulations and regretted that Marco Civil had not been adopted before the vote. While it is not unusual for any government to see a contradiction between domestic and foreign policy, Molon believed that the adoption of Marco Civil would have established without doubt Brazil’s policy and support for a transparent and inclusive approach to internet governance.

The reasons behind Brazil’s vote at the WCIT are obscure. First of all it is worth noting that most Latin American countries voted in favour of the text adopting new International Telecommunications Regulations. An analysis of the region’s vote shows that beyond governments’ intentions and goodwill towards the current multistakeholder governance model, to most Latin American governments, the new regulations were not about the internet but about telecommunications. Most of these governments would have looked at the new ITRs to “reap some of the benefits of the ITRs as a whole”, especially in terms of technical facilities. Second, like India, Brazil has increasingly expressed its desire to take on the US hegemony over the internet and digital technologies. The clash between the two sides revealed at WCIT 2012 led The Economist to call WCIT 2012 a “digital cold war”. Brazil’s position is, however, more complex. Neither a supporter of the US nor Sino-Russian initiatives, Brazil has been seeking greater recognition in multilateral forums and has called for the rebalancing of international institutions. As one of the new global economic powerhouses alongside Russia, India and China, but considered the most democratic of that group with India, aligning with countries supporting tighter government control was more a statement against internet governance by institutions seen as under US control – namely ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) – and an assertion of Brazil’s sovereignty.

The revelations on mass surveillance activities carried out by the US further fuelled Brazil’s will to break from US-centric internet. Standing against mass surveillance, Brazil distanced itself from the top-down internet governance approach and called for an “open, multilateral and democratic governance, carried out with transparency by stimulating collective creativity and the participation of society, governments and the private sector.”

Shortly after announcing the organisation of an international conference to discuss the future of internet governance in response to the surveillance revelations, President Dilma Rousseff also ordered a series of measures aimed at greater Brazilian online independence and security. But what are the internet governance implications of that opposition to the US spying? By trying to get away from the US dominance of the internet, Roussef’s measures risk taking a regressive stance on the internet. Paradoxically, while asserting internet freedoms, the geopolitics behind Brazil’s response to mass surveillance could align it with countries pushing for top-down internet control both nationally and internationally.

After Snowden: Brazil taking the lead and opposing mass surveillance – but at what cost?

In September 2013, President Dilma Rousseff made a strong political response to Snowden’s revelations on mass surveillance activities carried out by the United States. In a speech delivered to the UN General Assembly, Brazil’s president accused the NSA of violating international law and called on the UN to oversee a new legal system to govern the internet. Rousseff seized the momentum created by Snowden’s revelations to question the current multilateral mechanisms in place – such as ICANN – and announced that Brazil would host an international summit to discuss the future of internet governance in April 2014: NETmundial. ICANN has faced growing criticism in recent years about the influence of the US government on its operations. In this context, the efforts of Brazil in promoting digital freedom at domestic level with Marco Civil have helped the country gain a leading role and visibility in internet rights discussions. While India used to appear as a natural leader of the debate, discussions on Marco Civil and internet legislation have reached an international audience to the extent that Indian politicians now say “India has lost its leadership status to Brazil in the internet governance space”.

Not only is Brazil one of the countries with emerging influence in the multipolar world but it is also a state whose population is increasingly engaging with the internet. The decision to host NETmundial shows both Brazil’s stand against mass surveillance – at least officially – and its ambition to take the lead on internet governance debates.

The opposition to US-led mass surveillance led Brazil to propose a series of ambitious and controversial measures aimed at extricating the internet in Brazil from the influence of the US and its tech giants, in particular protecting Brazilians from the reach of the NSA. These included: constructing submarine cables that do not route through the US, building internet exchange points in Brazil, creating an encrypted email service through the state postal system and having Facebook, Google and other companies store data by Brazilians on servers in Brazil. While the first two were an attempt at developing internet infrastructure in Brazil, forcing tech giants to locate their data centres locally to process local communications would have big implications. Not only would it be very difficult to implement at a practical level, but it would not even protect Brazilians’ data from surveillance. On the contrary, data stored locally would be more vulnerable to domestic surveillance. This proposal – even made with good intent – was sending the wrong message, especially to other countries looking to Brazil as a leader in this space. Engineers and web companies, who have their own agenda and economic interests, argued it would have a negative impact on Brazilian competitiveness, would be damaging for its tech sector and pose a threat of “internet fragmentation”. In terms of internet freedom, the measure set a dangerous precedent. Indeed, forced localisation of data relates more to measures undertaken by countries that have a reputation of internet control and repressive digital environments, such as China, Iran and Bahrain.

At a time when Brazil is gaining international exposure for defending internet freedom, it is important to stick to a progressive internet governance approach, including at the international level. The international summit on the future of internet governance – NETmundial – kicked off with Brazil reiterating its commitment to a “democratic, free and pluralistic” internet. The signing of Marco Civil da Internet into law by the Brazilian president onstage set the tone of the event: “The internet we want is only possible in a scenario where human rights are respected. Particularly the right to privacy and to one’s freedom of expression,” said Dilma Rousseff in her opening speech. She added about Marco Civil: “As such, the law clearly shows the feasibility and success of open multisectoral discussions as well as the innovative use of the internet as part of ongoing discussions as a tool and an interactive discussion platform”.

The drafting process of Marco Civil and the inclusive consultation process that has involved civil society and private sector from beginning to end served as a model for the organisation of NETmundial. The unprecedented gathering brought together 1,229 participants from 97 countries. The meeting included representatives of governments, the private sector, civil society, the technical community and academics. Remote participation hubs were set up in cities around the world and the NETmundial website offered an online livecast of the meetings.

However, despite efforts to include civil society and despite Dilma Rousseff’s speech in favour of freedoms online and net neutrality, the geopolitics around the event and pressure from some governments and private sector led to a weak, disappointing outcome document. The final version of the “Internet governance principles” document did not even mention net neutrality – a fundamental principle of the internet architecture. Disappointed and frustrated, many internet activists launched a campaign asking governments to take concrete actions to end global mass surveillance and protect the free internet. Some even came to question the multistakeholder model of internet governance.

The multistakeholder model in question

Although the process for discussion adopted by NETmundial appeared inclusive, the multistakeholder model was criticised by internet activists and described as “oppressive, determined by political and market interests”. The balance of power and weak outcome document of NETmundial led them to call the principles of NETmundial “empty of content and devoid of real power”. La Quadrature du Net, which defends the rights and freedom of citizens on the web, called NETmundial international governance a “farce” and the multistakeholder approach an “illusion”.

Although Brazil made considerable efforts to offer an event open to civil society, academics, private sector and all governments, in reality the power of non-government actors, especially of civil society, is relatively weak next to the dominance of governments, tech giants and other powerful private corporations. And, as attractive as the rhetoric of liberty and freedom might be, intrusive governance is still regarded as acceptable by governments of all kinds – even those with apparently progressive attitudes towards an open internet. This is reinforced by fears of virtual crimes and cybersecurity, which are vital areas of government policy, as recently claimed by the Brazilian minister of communications Paulo Bernardo. In Brazil, as well as in India and other democracies, the balance between freedom and security can generate contradictory positions between international and domestic policies, and security arguments have often been used to justify claims for greater state control over critical internet resources, at the risk of falling into the game of repressive regimes.

The future of internet governance is still being discussed and Brazil is under the spotlight. It is not clear yet to what extent Marco Civil will lead to a safer and better online and offline environment. Meanwhile, Brazil should not support approaches that lead to top-down control of the net or forced local hosting of data. In the aftermath of NETmundial, Brazil appears more as a leader and influencer in the global debates on the future of internet governance. However, the outcome of NETmundial underlined Brazil’s vulnerability to pressure from the US, the EU and industrial interests. Brazil must continue to build on Marco Civil in the international sphere and use its clout to promote internet freedoms.

The full report is available in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Part 1 Towards an internet “bill of rights” | Part 2 Digital access and inclusion | Part 3 Brazil taking the lead in international debates about internet governance | Part 4 Conclusions and recommendations

This article was posted on 16 June 2014 at indexoncensorship.org