By Giles Strachan and Ilan Manor

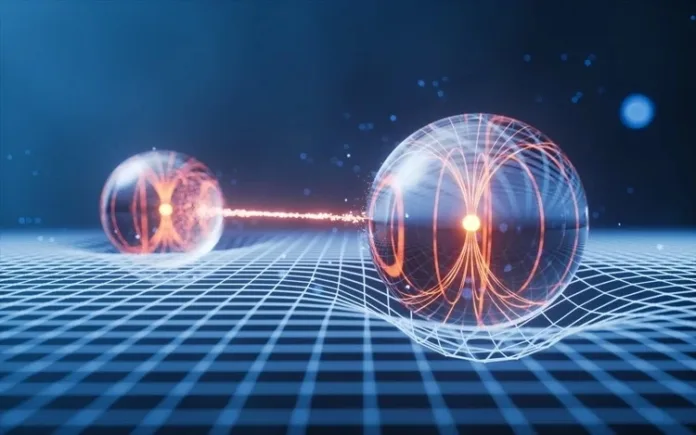

In 1957, the physicist Hugh Everett proposed the Many-worlds Interpretation of reality. Quantum physicists had discovered that fundamental information about particles was unknowable until the particles were observed. At this point, reality re-asserts itself, as in the famous example of Schrödinger’s cat, which is both alive and dead until observed. While physicists debated how these two competing realities came into existence, Everett cut the gordian knot with a simple proposal: there are multiple realities. The Many-worlds Interpretation has long existed as a scientific curio. Today, however, it is more relevant than ever.

In the aftermath of the recent crisis between India and Pakistan, MFAs scrambled to gather information. Clearly some form of military exchange had taken place, but the precise details were unclear. Along with the usual tools for disinformation – clips from the video game Arma 3, photos from other conflicts, shoddy photoshop jobs – a new form of misinformation emerged. On May 8th, a sophisticated deepfake purported to show Pakistani General Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry reporting the loss of two Pakistani jets. The report was picked up on Indian media channels and was viewing nearly one million times before being debunked. The speed with which good-quality fake videos can be produced and disseminated demonstrates that, thanks to artificial intelligence, we are facing greater challenges than ever in maintaining a single definition of reality.

AI has not changed the human propensity to misrepresent facts. A simple examination of the evolution of the Wikipedia page on, say, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, reveals that competing versions of reality have long sought to assert themselves. In the past, however, the fabrication of sophisticated evidence took time. Editing Trotsky out of photos with Lenin was a delicate task handled by specialist editors. Building fake news websites to spread stories about EU immigrants swamping British public services was easier, but still required time and money. Today, however, AI has made disinformation cheaper and easier to access than ever.

The challenge for diplomats is that diplomacy is fundamentally dependent on a shared definition of realities. As negotiations take place for a ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine, it is clear that there is a distinction between public and private positions. In public, Russia has made it abundantly clear that Ukraine is a Nazi-run state which must be thoroughly cleansed of all anti-Russian elements. Meanwhile, Ukraine is implacably opposed to any settlement other than the return of pre-2014 borders, including Crimea. Clearly, no ceasefire would be possible if those positions were maintained in private.

The art of negotiation is the ability to soften these stances in such a way that both sides can achieve a satisfactory resolution – in short, to achieve a shared vision of reality in which both sides acknowledge their inability to achieve their objectives through conflict. If diplomats are unable to do so, then negotiations cannot succeed.

This search for a shared definition of reality dictates how negotiations are conducted. Diplomats may not change their definition of reality in front of news cameras, but within the privacy of the negotiation chamber, they can soften the edges of their position to achieve a settlement. Such was the case in 2014 when, despite public claims to the contrary, a Russian diplomat could acknowledge that ‘some’ Russian troops had crossed into Crimea.

Achieving a shared definition of reality requires significant skill and hard work but is also dependent upon reliable data for decision-makers and a supportive political environment. The spread of AI-generated misinformation undermines both. The former is clearly challenged by the proliferation of open-source misinformation. The latter is also a victim of AI – users of social media can increasingly maintain a supply of increasingly sophisticated content that reinforces their worldview. Under the influence of their feed, they may resist diplomatic settlements that contradict their interpretation of reality. An Indian public which believes that India has shot down two Pakistani jets may consider themselves to have the upper hand in military affairs and thus resist a peaceful de-escalation of tensions.

Beyond these short-term scenarios, AI brings a further challenge in the form of virality. In February, Donald Trump shared an AI-generated video showing himself and Benjamin Netanyahu dancing at the Trump Gaza resort. Although clearly fake, the video nonetheless demanded a diplomatic response. Was it simply a ghoulish joke, or a signal of a long-term plan? Do MFAs lose credibility when responding to clearly fake videos, or is it necessary to re-affirm negotiating positions even in the face of such an absurd proposal?

Once again, AI has not given Donald Trump any greater desire to sow chaos on social media. The sophistication of these tools, however, allows for content that can go viral in a way that a written tweet could not, and that can be generated by comparatively untrained users in a short space of time. The absurdity and novelty of the video drove its popularity. As the sophistication of AI grows, we should expect to see more of these videos, forcing diplomats to spend more time and energy responding to artificially-generated content.

The proliferation of AI is the proliferation of parallel universes. Whether in the form of persuasive deepfakes or absurdist humour, AI is enabling a proliferation of competing realities. For regular users, the seductive appeal of a vision of reality tailored entirely to one’s own beliefs is enough to influence political decision-making. Without a supportive political environment, diplomats will face greater pressure to maintain public rhetoric and will struggle to sell negotiated settlements to their domestic audiences. Simultaneously, diplomats themselves face greater challenges as AI makes it increasingly difficult to establish what has actually happened. By the time a diplomat has established whether or not a video is fake, it is too late. An endless number of plausible realities, generated as fast as prompts can be typed, will provide plausible evidence in support of mutually-exclusive versions of reality.

In this scenario, there is a risk that diplomats will use AI to counter AI – for example, in drafting customised responses to misinformation. In this scenario, an MFA’s public position would be tailored to individual groups of users in an attempt to reach a wider audience. Under such a scenario, however, diplomacy would be surrendering to a fractured reality. Instead of attempting to assert a single, shared reality, MFAs would be accepting defeat. Amid a cascade of differing realities, they may long for the comparative peace of the negotiating room.

(@francediplo_EN)

(@francediplo_EN)  (@MFA_Ukraine)

(@MFA_Ukraine)  | #StandWithUkraine

| #StandWithUkraine