Section 15(1) of the Diplomatic Immunities and Privileges Act 37 of 2001 (the Act) creates an offence if anyone obtains or executes any legal process against diplomats. It is noteworthy that a party to such proceedings, an attorney and the Sheriff are specifically referred to therein. Should s 15(1) be contravened or if any other offence is committed resulting in the infringement of a diplomat’s personal inviolability or that of their property or residence, the offender could, on conviction, be fined and/or imprisoned for up to three years (s 15(2) of the Act).

In light of the far-reaching implications of s 15, I will attempt to explain the nature, effects and implications of what is known as ‘diplomatic immunity’ in order to assist members of the profession not to fall foul of its provisions. In doing so, I will first examine the purpose of immunity, thereafter, the difference between state (or sovereign) immunity and diplomatic immunity will be highlighted. Lastly, I will identify the different types of immunity, as well as the implications of each.

Immunity from?

The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961 (VCDR) has the force of law in South Africa (SA) (s 2(1) of the Act) and applies to all diplomatic missions and members of such missions in SA (s 3(1) of the Act). The VCDR provides a complete framework for the establishment, maintenance and termination of diplomatic relations. Moreover, it not only codifies pre-existing principles of customary international law relating to diplomatic immunity, but resolves points on which differences among states had previously meant that there was insufficient consensus to create a rule of customary international law. The Preamble of the VCDR also states that the purpose of diplomatic immunity is to ‘ensure the efficient performance of the functions of diplomatic missions as representing States’. Its main aim is to shield diplomats from actions interfering with the performance of their official duties in the receiving state (refer to the fourth recital of the VCDR).

Immunity of this nature is procedural in character and does not affect any underlying substantive liability (Portion 20 of Plot 15 Athol (Pty) Ltd v Rodrigues 2001 (1) SA 1285 (W) at 1293 G – I; Democratic Republic of the Congo v Belgium (Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000) [2002] ICJ Rep 3 at paras 59 – 61). This principle is essential as the receiving state cannot at the same time receive a foreign diplomat by mutual consent (art 2 of VCDR) and then subject such diplomat to the authority of its own courts in the same way as other persons within its territorial jurisdiction. Diplomats, however, are not exempt from the jurisdiction of their own countries’ courts (art 31.4 of VCDR) and, in important respects, to the jurisdiction of the courts of the receiving state after their posting has ended (art 39 of VCDR). It is noted that s 110A of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 ensures that South African diplomats who are immune from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving state could under certain circumstances be prosecuted in our courts if they commit offences during their tour of duty.

State immunity

The doctrine of state or sovereign immunity refers to the immunity, which one state enjoys within the jurisdiction of another state, which flows from the public international law principle of the equality of sovereign states or par in parem non habet imperium. This means that a sending state, which incurred legal liability in the receiving state, cannot under certain circumstances be summoned before the receiving state’s courts to be judicially forced to discharge its liability. The majority of states nowadays apply the doctrine of restrictive sovereign immunity, which distinguishes between non-sovereign acts, such as commercial transactions (so-called acta iure gestiones) and acts performed in the exercise of sovereign authority – the so-called ‘acts of state’ or acta iure imperii. The former does not entitle a sending state to immunity within the jurisdiction of the receiving state. South Africa, by promulgating the Foreign States Immunities Act 87 of 1981, followed suit and based it to a large extent on the United Kingdom’s State Immunity Act 1978.

Diplomatic and state immunity have a number of points in common –

- both are immunities of the state, which can be waived only by the state;

- both may extend to individual agents of the state, acting as such;

- both are creatures of international law; and

- although only diplomatic immunity has been codified by treaty, the embryonic United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States is generally regarded as an authoritative statement of customary international law on the major points which it covers.

As will be seen below, the immunity of diplomatic agents are wider than those of the state because their purpose is to remove persons who are within the receiving state’s territory and under its physical power from its jurisdiction (Elieen Denza, Diplomatic Law: Commentary on the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations 4ed (Oxford University Press 2016) at 1; Reyes v Al-Malki and Another [2017] UKSC 61 at para 27 – 28).

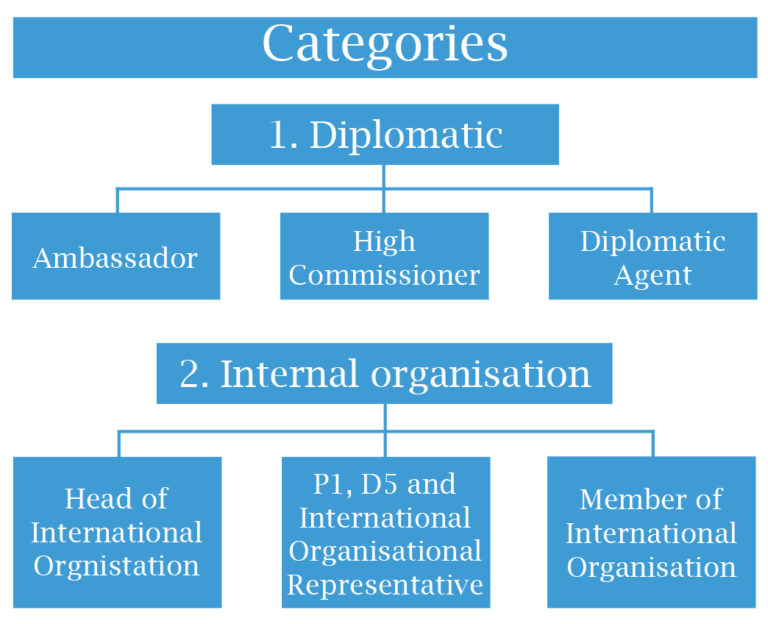

Immunity enjoyed by diplomatic agents, consular officers and other mission personnel

Diplomatic immunity is dealt with in art 22 and 29 to 40 of the VCDR. These provisions confer different degrees of immunity on persons connected with a diplomatic mission according to their status and function. The VCDR distinguishes between diplomatic agents (ie, heads of mission and members of their diplomatic staff) the administrative and technical staff of the mission, their respective families and service staff of the mission.

- Diplomatic agents

The highest degree of protection is conferred on diplomatic agents and is virtually absolute. In the case of diplomatic agents, the VCDR substantially reproduces the previous rules of customary international law, by which a diplomatic agent was immune from the jurisdiction of the receiving state, namely –

- in respect of things done in the course of their official functions for an unlimited period; and

- in respect of things done outside their official functions for the duration of his mission only.

Thus, art 31.1 confers immunity on currently serving diplomatic agents in respect of both private and official acts, subject to specific exceptions for three designated categories of private acts (see art 31.1(a) to (c)). Diplomatic agents enjoy the following immunity –

- personal inviolability (art 29);

- inviolability of their official residence (art 22.1 and 30.1);

- inviolability of their papers, correspondence and property (art 30.2);

- immunity from the criminal, civil and administrative jurisdiction of the receiving state (art 31.1); and

- non-compellable witness (art 31.2).

As a result, the representatives of the receiving state cannot arrest or detain diplomatic agents and their residences, property or persons are immune from search, requisition, attachment or execution due to their personal inviolability. A summons or warrant cannot be served on them personally, nor on their residences, or the mission. For more detail in this respect, refer to Riaan de Jager ‘Diplomatic law: Service of process on foreign defendants’ 2017 (Dec) DR 34. Also, they cannot be charged in the criminal courts, nor sued in the civil or administrative courts of the receiving state. The reason: What a diplomatic agent does in the course of his official functions is done on behalf of the sending state and is an act of the sending state, although it may give rise to personal liability on the part of the individual agent. Any acts that a diplomatic agent performs in a personal or non-official capacity are, however, not acts of the state that employs them. The right to assert immunity in this respect can only be justified on the practical ground that their exposure to civil or criminal proceedings in the receiving state, irrespective of the justice of the underlying allegation, could impede the functions of the mission.

Because diplomatic missions are usually situated in the capital of the receiving state, all such missions in SA are located in Pretoria (Tshwane).

- Diplomatic agents’ family members

Diplomatic agents’ family members forming part of their households will in terms of art 37.1 enjoy the same immunity. The justification for it is to protect diplomats from harassment particularly by means of framed or politically motivated legal proceedings so that they can perform their functions whatever the situation in the receiving state (Denza (op cit) at 320).

- Administrative and technical staff

Members of the administrative and technical staff of the mission, together with their family members, enjoy their immunity in terms of art 37.2 includes –

- personal inviolability (art 29);

- inviolability of their private residence (art 30.1);

- inviolability of their papers and correspondence (art 30.2);

- immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving state (art 31.1);

- immunity from the civil and administrative jurisdiction of the receiving state with regard to acts performed in the course of their official duties (art 31.1); and

- non-compellable witness (art 31.2).

It is evident that these members enjoy the same immunities as diplomatic agents except for immunity from the civil and administrative jurisdiction regarding acts performed ‘outside the course of their duties’. They can never be tried on a criminal charge in any circumstances (unless their immunity is expressly waived), but they may be sued on personal matters.

- Service staff

Members of the service staff of the mission who are not nationals of or permanently resident in the receiving state only enjoy immunity in respect of acts performed in the course of their duties (art 37.3) – this is known as functional immunity.

- Consular officers

The immunity that consular officers enjoy in terms of international law are regulated by the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 1963 (VCCR), which also has the force of law in SA (s 2(1) of the Act). These officers are attached to consular posts (eg, Consulates-General, trade offices, etcetera) in cities outside Pretoria (Tshwane) (eg, Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, etcetera). Unlike the almost absolute immunity, which diplomatic agents and their family members enjoy in terms of the VCCR, consular officers only enjoy functional immunity which is limited to –

- immunity from arrest or detention pending trial except in case of a grave crime and pursuant to a court order (art 41);

- immunity from the jurisdiction of the judicial or administrative authorities of the receiving state in respect of acts performed in the exercise of consular functions (art 43.1); and

- although they may be called on to attend as witnesses in the course of judicial or administrative proceedings, no coercive measure or penalty may be applied to them if they decline to do so (art 44.1).

It is worth noting that the members of the family of consular officers forming part of their households do not enjoy any immunity whatsoever.

- Intergovernmental organisations

The immunities that officials attached to representative offices of intergovernmental organisations (eg, the African Union, United Nations, International Labour Organisation, etcetera) in SA enjoy are set out in the various host agreements, which such organisations conclude with the South African government. With the exception of the most senior representatives of such organisations, who usually enjoy full diplomatic immunity, these officials only enjoy functional immunity.

Abuse of status by diplomats

Despite their immunity, diplomats are under a duty to respect the laws and regulations of the receiving state (art 41.1 of the VCDR and art 55.1 of the VCCR). Where any law or regulation has been breached, the receiving state has the following remedies:

- Request an official apology from the sending state by way of note verbale.

- Request the sending state to waive the offending diplomat’s immunity (s 8 of the Act, read with art 32.1 and 32.2 of VCDR or art 45 of VCCR).

- Request the sending state to recall the offending diplomat.

- Declare such diplomat undesirable or persona non grata.

- Deregister the diplomat from accreditation and request their immediate departure from its territory.

Since all accredited diplomats are registered with the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO) (s 9(2) of the Act), its Chief of State Protocol is empowered by s 9(3) to issue a certificate on request to clarify whether a person enjoys immunity. Before taking any measures against a person who might enjoy immunity or inviolability, attorneys are advised to approach the Directorate: Diplomatic Immunities and Privileges of DIRCO for confirmation of their status.

Riaan de Jager BLC LLB LLM (UP) Advanced Diploma (Labour Law) (RAU) is a Principal State Law Adviser (International Law), attached to the Office of the Chief State Law Adviser (International Law) and the Department of International Relations and Cooperation in Pretoria.

This article was first published in De Rebus in 2018 (July) DR 26.

By Riaan de Jager