Evan Kraus is executive director of digital strategy at APCO Online®, a service group that delivers powerful, results-focused online communication strategies for APCO Worldwide’s clients around the world. This post originally appeared in the Diplomatic Courier.

Evan Kraus is executive director of digital strategy at APCO Online®, a service group that delivers powerful, results-focused online communication strategies for APCO Worldwide’s clients around the world. This post originally appeared in the Diplomatic Courier.

Walk the streets of any big city today, anywhere in the world, and it is impossible to miss the impact of digital communication technology on nearly every aspect of our daily lives. It impacts the way we communicate, socialize, travel, are entertained, buy products and services, and even find our life partners. But, what about diplomacy, that famously nuanced, human talent that is so deeply rooted in a face-to-face, personal connection? How has digital changed the diplomacy

To understand the imprint digital has made on diplomacy, we first need to understand the psychology of digital natives. It is a human nature to try and make a difference in the world around us; to seek something more. Media, particularly digital media, offers a level of transparency and direct access that gives political activists, thought leaders and influencers the ability to force political change. Just as social media has removed the power of traditional reporters to serve as the primary connectors between news-making principals and the public, it has also diminished the power of traditional political gatekeepers.

NGOs and activist groups were the first movers in harnessing this power to impact political change. Underfunded and outmanned by corporations and their agents, these groups took to the digital streets to create political movements and, in many cases, were able to enact real change.

Inspired by these examples and their own experiences, individual citizens realized they could create their own movements. Whether it be a customer like Molly Katchpole, who used Change.org and a passionate letter to convince a major U.S. bank to withdraw a debit card fee; a citizen like Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor whose shocking act of self-immolation captured on YouTube sparked the Arab Spring; or the director Jason Russell whose short film Kony 2012 began a campaign to raise the visibility about forced recruitment of child soldiers in Africa and motivated millions (including celebrities and political figures) to call for the arrest of Joseph Kony and push to enact new policies and change. These empowered activists have inspired uprisings that change the world.

Although slower to the party, the traditional power brokers in society–corporations and policymakers themselves–have learned how to harness the power of digital and social media to their own political benefit. It is now fairly routine for political figures around the world to directly engage with the public on social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. During President Obama’s reelection campaign, his “Ask Me Anything” feature on Reddit quickly broke traffic and engagement records for the platform and connected him directly with his audience without any gatekeepers. Communicating via social media can also have a real impact on society. As an example, my company APCO Worldwide helped a government transform how it communicated with the public. We educated its agencies on effectively engaging and connecting with citizens through activities and initiatives hosted through these channels. We also routinely help our corporate clients pursue and enact policy change in all corners of the world using the strategic application of digital diplomacy.

Underlying all of this are some basic principles that are hallmarks of almost every successful digital diplomacy initiative:

- Digital diplomacy is emotive: People in digital and social channels discuss and debate issues with their emotions at the surface. The best campaigns are like great marketing campaigns that stir emotions, tell compelling stories and use pictures, videos, animation and graphic content to make arguments instead of studies and papers.

- Digital diplomacy is about pursuing a shared vision: The best digital diplomacy initiatives tap deep into an underlying tension or desire felt by a segment of society. It is not sufficient to just express your position well; your position must reinforce this more broadly felt societal goal.

- Digital diplomacy is transparent: In digital and social channels there is nowhere to hide. Attempts to communicate in ways that are perceived as inauthentic or contrived are doomed to fail.

- Digital diplomacy speaks directly to individuals: Although the web audience is enormous, digital and social media is actually comprised of millions of interconnected communities that form around shared ideas. The best campaigns carefully target those communities and recruit support by tailoring the appeal to the specific interests of their members. This process has been aided tremendously in recent years by the prevalence of “big data” and sophisticated tools to micro-target our messages.

- Digital diplomacy must be remarkably agile: Things change fast online. Ideas morph, change agents emerge and new information appears on a moment’s notice. Digital diplomacy campaigns must be carefully managed to respond quickly to those changes so they stay relevant, responsive and impactful.

The pace at which communication tools, techniques, platforms and strategies are changing can be dizzyingly fast. But, if you can stay grounded in these core principles, and remember that digital communication is simply a reflection of basic human emotions and impulses, you can have a tremendous impact on the world around your business, your organization and yourself.

http://www.apcoforum.com/diplomacy-in-a-digitally-infused-world/

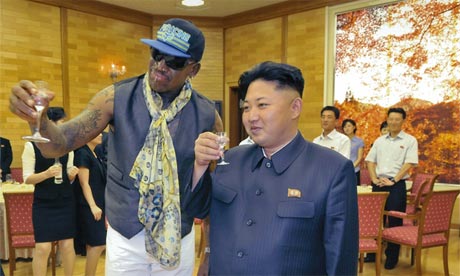

It is a time-honored tradition to use athletes as diplomats. They are some of the most recognizable global personages whose participation can lead to substantial bilateral benefits. In the 1970s, for example, U.S. President Nixon successfully promoted a team of American pingpong players to open up a dialogue with Mao Zedong’s China.

It is a time-honored tradition to use athletes as diplomats. They are some of the most recognizable global personages whose participation can lead to substantial bilateral benefits. In the 1970s, for example, U.S. President Nixon successfully promoted a team of American pingpong players to open up a dialogue with Mao Zedong’s China.