Humanitarian aid adds incentives for migrants to take risks in fleeing homelands

Italian elementary students attend the commemoration ceremony for the victims of the boat sinking disaster off the Lampedusa coast on Oct. 21, in San Leone near Agrigento, Italy. The disaster killed more than 300 asylum seekers. (Tullio M. Puglia/Getty Images)

A challenge with tighter borders and deportation is differentiating the asylum seekers from economic migrants.

The drowning of hundreds of men, women, and children off the coasts of Italy and Malta has brought world attention back to the dilemma faced by the developed world from desperation migration.

While humanitarian aid and favorable receptions to illegal immigrants willing to risk their lives to reach their intended destination are admirable and consistent with international conventions, these also add to the “pull factor”—adding incentives for human smugglers and encouraging more men, women, and children to undertake perilous journeys.

Although deaths attributable to desperation migration are incomplete, available data for certain regions provides a crude approximation of the minimum levels. In the past two decades, for example, nearly 20,000 people are reported as having lost their lives in an effort to reach the European Union’s southern borders from Africa and the Middle East. In 2011 at the height of the Arab Spring more than 1,500 died in efforts to reach the southern shores of the EU with close to 300,000 registered asylum claims.

Also, attempts to cross the United States–Mexico border resulted in close to 2,000 people dying during the period 1998–2004, with 477 deaths recorded and more than 83,000 registered asylum claims in the past year. In addition, the number of deaths or persons missing at sea trying to reach Australia since 2000 is recorded at 1,731, with 242 for the year 2012 and nearly 16,000 registered asylum claims.

Responding to Dire Situations

When people face dire times, many try migrating to more prosperous, favorable, or sparsely populated lands. Over the past two centuries, tens of millions of men, women, and children migrated from Europe to North America, South America, and Oceania.

During the Irish Potato Famine, for example, more than a million emigrated from Ireland. Poverty, natural disasters, overpopulation, and political unrest contributed to 2 million Italians migrating to the United States in the first decade of the 20th century. Travel then was difficult and costly, and processing was a formality.

Opportunities for large-scale migration have come to a close. Established borders, national laws and international agreements, nationalism, security concerns, technology as well as striking economic, social, and demographic imbalances all contribute to limiting immigration levels to the needs and wellbeing of the receiving countries.

Few governments wish to increase current levels of immigration. Close to 75 percent of national governments have policies to maintain current immigration levels. Another 16 percent of governments have policies to lower immigration. Only 10 percent plan to increase immigration levels, and those policies are aimed primarily at attracting highly skilled technical workers.

Given limited opportunities for legal migration and increased border surveillance, growing numbers turn to professional smugglers. The risks of these hazardous journeys are both minimized and understood by would-be migrants, who compare them to bleak, often precarious living conditions at home.

Many immigrants flee civil conflict, political violence, and persecution. Others risk their lives to escape poverty and provide remittances to those left behind. Many who migrate for economic reasons and survive clandestine passage claim asylum upon arrival to avoid being sent back home, complicating matters for genuine refugees.

According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, more people are refugees or internally displaced than at any time since 1994, with the crisis in Syria resulting in more than 2 million people fleeing the country.

Approximately 32,000 people have arrived unlawfully in southern Italy and Malta this year alone and around two-thirds have filed requests for asylum. In addition, the reported number of migrants leaving Libya for Europe has seen a sixfold increase over the last year.

While the majority of the illegal migrants come from sub-Saharan Africa, during the current year greater numbers have arrived from Egypt and Syria. Continued degradation of living standards in Iran hit by Western sanctions has propelled large numbers to migrate to Australia by boat from Indonesia.

Open Borders or Closed

Curtailing desperation migration is challenging the policies of receiving and transit governments as well as public sentiments, especially in the destination countries.

Some academics and theorists suggest the only solution to desperation migration is for countries to institute open borders. Similar to the free flow of capital across national borders, advocates of open borders argue that people should have the right to freely cross international borders to travel, work, visit, open businesses, settle, and interact with others.

In striking contrast, many governments, political parties, and nativist groups argue for more effective controls on entry and strict enforcement of immigration laws, especially penalties for those who hire illegal immigrants. Opponents of open immigration support prosecution of human smugglers and detention and expedited removal of illegal immigrants—regarded as predominately economic migrants—to their points of departure or country of origin.

In particular, the opponents consider fences, walls, and barriers coupled with increased border surveillance, including the use of satellite imagery and drones to monitor borders, as effective preventive measures to discourage people from undertaking hazardous journeys and thus save lives. Such policies have become increasingly evident in Australia, Canada, Greece, India, Israel, Italy, Malta, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, and the United States.

The emphasis on policies of “prevention through deterrence” has increased pressures on authorities in transit countries like Libya and Morocco and strained limited resources to curb illegal migration flows.

Safer Passage

Few disagree that more must be done to reduce migrant deaths. Under such an approach, countries would be obliged to protect, respect, and fulfill human rights of legal as well as illegal migrants. In particular, border guards, coastguards, air patrols, and commercial ships should have the capability and commitment to provide humanitarian assistance and save lives, whether off the shores of Italy or northern Australia.

A fundamental difficulty with tighter borders and the deportation approach is differentiating asylum seekers, genuinely in need of international protection, from economic migrants who seek employment, higher wages, and a better life. With receiving countries becoming more selective, the large numbers of potential migrants in developing countries, in particular the growing pool of the unskilled and poorly educated, are finding few if any legal means to secure employment and settle abroad.

Even doubling the current levels of legal immigration would unlikely reduce the illegal flows. Whereas current migration flows are several million per year, the would-be number of migrants seeking to escape unemployment, poverty, economic collapse, political turmoil, war, and persecution can be expected to be many times greater.

In addition to migration push factors, strong pull factors in the destination countries include a demand for cheap and compliant illegal labor, especially for jobs that cannot be outsourced in agriculture, food processing, landscaping, restaurant work, construction, child care, and domestic services.

Although desperation migration has again attracted world attention, the international community of nations is not actively seeking to identify concrete solutions. The recent two-day United Nations High Level Dialogue on International Migration and Development, for example, simply noted the recent drowning of hundreds of migrants off the coast of Italy. The sole outcome of the dialogue was a summary of the deliberations, devoid of binding agreements on international migration or recommendations addressing desperation migration.

Tragically, given the current worrisome state of economic, social and political affairs in many developing countries, and the reluctance of most migrant-receiving nations to engage in a meaningful international dialogue on desperation migration, many more migrant deaths can be expected in the near future.

Joseph Chamie is a former director of the United Nations Population Division. Copyright 2013 The Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale.

http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/365932-the-dilemma-of-desperation-migration/

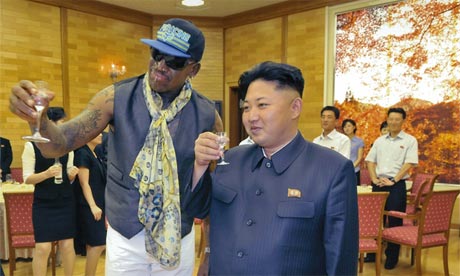

It is a time-honored tradition to use athletes as diplomats. They are some of the most recognizable global personages whose participation can lead to substantial bilateral benefits. In the 1970s, for example, U.S. President Nixon successfully promoted a team of American pingpong players to open up a dialogue with Mao Zedong’s China.

It is a time-honored tradition to use athletes as diplomats. They are some of the most recognizable global personages whose participation can lead to substantial bilateral benefits. In the 1970s, for example, U.S. President Nixon successfully promoted a team of American pingpong players to open up a dialogue with Mao Zedong’s China.